The pituitary gland is a pea-sized structure located at the base of the brain, just below the hypothalamus and attached to it with pituitary stalk through which hypothalamus control the function of pituitary gland. The pituitary gland controls the function of most other endocrine glands and is therefore sometimes called the master gland. The pituitary is divided into three sections: the anterior, intermediate, and posterior lobe. Anterior lobe hormones.

The anterior lobe of the pituitary produces and releases (secretes) six main hormones:

- Growth hormone, which regulates growth and physical development and has important effects on body shape by stimulating muscle formation and reducing fat tissue

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone, which stimulates the thyroid gland to produce thyroid hormones

- Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), also called corticotropin, which stimulates the adrenal glands to produce cortisol and other hormones

- Follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone (the gonadotropins), which stimulate the testes to produce sperm, the ovaries to produce eggs, and the sex organs to produce sex hormones (testosterone and estrogen)

- Prolactin, which stimulates the mammary glands of the breasts to produce milk

Posterior lobe hormones

The posterior lobe of the pituitary produces only two hormones:

- Vasopressin

- Oxytocin

Vasopressin(also called antidiuretic hormone) regulates the amount of water excreted by the kidneys and is therefore important in maintaining water balance in the body.

Oxytocin causes the uterus to contract during childbirth and immediately after delivery to prevent excessive bleeding. Oxytocin also stimulates contractions of the milk ducts in the breast, which move milk to the nipple (the let-down) in lactating women.

Pituitary gland malfunction

The pituitary gland can malfunction in several ways, usually as a result of developing a noncancerous tumor (adenoma). The tumor may overproduce one or more pituitary hormones, or the tumor may press on the normal pituitary cells, causing underproduction of one or more pituitary hormones.

The tumor may also cause enlargement of the pituitary gland, with or without disturbing hormone production. Sometimes there is overproduction of one hormone by a pituitary tumor and underproduction of another at the same time due to pressure.

Sometimes excess cerebrospinal fluid can fill the space around the pituitary gland and compress it (resulting in empty sella syndrome). The pressure may cause the pituitary to overproduce or underproduce hormones.

Too little or too much of a pituitary hormone results in a wide variety of symptoms.

Disorders that result from overproduction of pituitary hormones include

- Acromegaly or gigantism: Growth hormone

- Galactorrhea: Prolactin

- Erectile dysfunction: Prolactin

Disorders that result from underproduction of pituitary hormones include

- Central diabetes insipidus: Vasopressin

- Hypopituitarism: Multiple hormones

Doctors can measure the levels of pituitary hormones, usually by a simple blood test

Pituitary adenomas

These benign tumors do not spread outside the skull. They usually remain confined to the sella turcica (the tiny space in the skull that the pituitary gland sits in). Sometimes they grow into the walls of the sella turcica and surrounding blood vessels, nerves, and coverings of the brain. They don’t grow very large, but they can have a big impact on a person’s health.

There is very little room for tumors to grow in this part of the skull. Therefore, if the tumor becomes larger than about a centimeter (about half an inch) across, it may grow upward, where it can compress and damage nearby parts of the brain and the nerves that arise from it. This can lead to symptoms such as vision changes or headaches.

Pituitary adenomas can be divided into 2 categories based on size:

- Microadenomas are tumors that are smaller than 1 centimeter (cm) across. Because these tumors are small, they rarely damage the rest of the pituitary or nearby tissues. But they can cause symptoms if they make too much of a certain hormone.

- Macroadenomas are tumors 1 cm across or larger. Macroadenomas can affect a person’s health in 2 ways. First, they can cause symptoms if they make too much of a certain hormone. Second, they can cause symptoms by pressing on normal parts of the pituitary or on nearby nerves, such as the optic nerves.

- Functional versus non-functional adenoma

- Pituitary adenomas are also classified by whether they make too much of a hormone and, if they do, which type they make. If a pituitary adenoma makes too much of a hormone it is called functional. If it doesn’t make enough hormones to cause problems it is called non-functional.

Functional adenomas: Most of the pituitary adenomas that are found make excess hormones. The hormones can be detected by blood tests or by tests of the tumor when it is removed with surgery. Based on these results, adenomas are classified as:

- Prolactin-producing adenomas (prolactinomas), which account for about 4 out of 10 pituitary tumors

- Growth hormone-secreting adenomas, which make up about 2 in 10 pituitary tumors

- Corticotropin (ACTH)-secreting adenomas (about 5% to 10%)

- Gonadotropin (LH and FSH)-secreting adenomas (less than 1%)

- Thyrotropin (TSH)-secreting adenomas (less than 1%)

Non-functional adenomas: Pituitary adenomas that don’t make excess hormones are called non-functional adenomas or null cell adenomas. They account for about 3 in 10 of all pituitary tumors that are found. They are usually detected as macroadenomas, causing symptoms because of their size as they press on surrounding structures.

Signs and Symptoms of Pituitary Tumors:

Not all pituitary tumors cause symptoms.

- The first symptoms often depend on whether the tumor is functional(releasing excess hormones) or non-functional (not releasing excess hormones) and micro or macroadenoma

- Functional adenomas can cause problems because of the hormones they release.

- Small Non-functional adenomas that cause no symptoms are sometimes found because of an MRI or CT scan done for other rea

- Tumors that aren’t making excess hormones often become large (macroadenomas) before they are noticed. These tumors cause symptoms when they press on nearby nerves, parts of the brain, or other parts of the pituitary.

Large tumors (macroadenomas)

- Blurred or double vision

- Loss of peripheral vision

- Sudden blindness

- Headaches

- Facial numbness or pain

- Dizziness

- Loss of consciousness (passing out)

Macroadenomas can also press on and destroy the normal parts of the pituitary gland, causing a shortage of one or more pituitary hormones. This can lead to low levels of some body hormones such as cortisol, thyroid hormone, and sex hormones. Depending on which hormones are affected, the symptoms might include:

- Nausea

- Weakness

- Unexplained weight loss or weight gain

- Feeling cold

- Feeling tired or weak

- Menstrual changes or loss of menstrual periods in women

- Erectile dysfunction (trouble with erections) in men

- Decreased interest in sex, mainly in men

Diabetes insipidus: Large tumors can sometimes press on the posterior pituitary, causing a shortage of the hormone vasopressin (also called anti-diuretic hormone or ADH). This can lead to diabetes insipidus. In this condition, too much water is lost in the urine, so the person urinates often and becomes very thirsty as the body tries to keep up with the loss of water. If left untreated, this can cause dehydration and abnormal blood mineral levels, which can lead to coma and even death. Fortunately, this condition is easily treated with a drug called desmopressin, which replaces the vasopressin. (Diabetes insipidus is not related to diabetes mellitus, in which people have high blood sugar levels.)

Growth hormone-secreting adenomas

In children, high GH levels can stimulate the growth of nearly all bones in the body. The medical term for this condition is gigantism. Its features typically include:

- Being very tall

- Very rapid growth

- Joint pain

- Increased sweating

In adults, the long bones (especially in the arms and legs) can’t grow any more, even when GH levels are very high. But bones of the hands, feet, and skull can grow throughout life. Adults with GH-secreting adenomas don’t grow taller and develop gigantism. Instead, they develop a different condition called acromegaly. The signs and symptoms are:

- Growth of the skull, hands, and feet, leading to increase in hat, shoe, glove, and ring size

- Deepening of the voice

- Change in how the face looks (due to growth of facial bones)

- Wider spacing of the teeth and protruding jaw (due to jawbone growth)

- Joint pain

- Increased sweating

- High blood sugar or even diabetes mellitus

- Kidney stones

- Heart disease

- Headaches

- Thickening of tongue and roof of mouth, leading to sleep disturbances such as snoring and sleep apnea (pauses in breathing)

- Thickened skin

- Increased growth of body hair

Corticotropin (ACTH)-secreting adenomas

High ACTH levels cause the adrenal glands to make steroid hormones such as cortisol. Having too much of these hormones causes symptoms that doctors group together as Cushing’s syndrome. When the cause is too much ACTH production from the pituitary it is termedCushing’s disease. In adults, the symptoms can include:

- Unexplained weight gain (mostly in the chest and abdomen)

- Purple stretch marks on the abdomen

- New or increased hair growth (on the face, chest, and/or abdomen)

- Swelling and redness of the face

- Acne

- Fat areas near the base of the neck

- Moodiness or depression

- Easy bruising

- High blood sugar levels or even diabetes mellitus

- High blood pressure

- Decreased interest in sex

- Changes in menstrual periods in women

- Weakening of the bones, which can lead to osteoporosis or even fractures

Prolactin-secreting adenomas (prolactinomas)

Prolactinomas are most common in young women and older men. In women before menopause, high prolactin levels cause menstrual periods to become less frequent or to stop. High prolactin levels can also cause abnormal breast milk production, called galactorrhea. In men, high prolactin levels can cause breast growth, erectile dysfunction (trouble with erections), and loss of interest in sex.

If the tumor continues to grow, it can press on nearby nerves and parts of the brain, which can cause headaches and vision problems. In females who don’t have periods (such as girls before puberty and women after menopause), prolactinomas might not be noticed until they cause these syThyrotropin (TSH)-secreting adenomas.

These rare tumors make too much thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), which then causes the thyroid gland to make too much thyroid hormone. This can cause symptoms of hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid), such as:

- Rapid heartbeat

- Tremors (shaking)

- Weight loss

- Increased appetite

- Feeling warm or hot

- Sweating

- Trouble falling asleep

- Anxiety

- Frequent bowel movements

- A lump (enlarged thyroid) in the front of the neck symptoms.

Gonadotropin-secreting adenomas

These uncommon tumors make luteinizing hormone (LH) and/or follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). This can cause irregular menstrual periods in women or low testosterone levels and decreased interest in sex in men.

Many gonadotropin-secreting adenomas actually don’t make enough hormones to cause symptoms, so they are basically non-functional adenomas. These tumors may grow large enough to cause symptoms such as headaches and problems with vision before they are detected (see the symptoms for large tumors above).

Tests to check endocrine function may be ordered, including:

- Cortisol levels: dexamethasone suppression test, urine cortisol test

- FSH level

- Insulin growth factor-1 (IGF-1) level

- LH level

- Prolactin level

- Testosterone/estradiol levels

- Thyroid hormone levels: free T4 test, TSH test

Tests that help confirm the diagnosis include the following: - Visual fields

- MRI of head

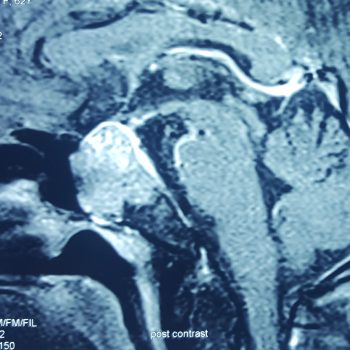

1. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). An MRI uses magnetic fields, not x-rays, to produce detailed images of the body. MRI can also be used to measure the tumor’s size. A special dye called a contrast medium is given before the scan to create a clearer picture. This dye can be injected into a patient’s vein or given as a pill to swallow. MRI is better than a computed tomography scan, which is described below, to diagnose most pituitary gland tumors, and it is now the standard method.

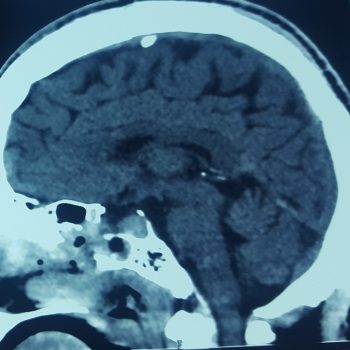

2. Computed tomography (CT or CAT) scan. A CT scan creates a 3-dimensional picture of the inside of the body using x-rays taken from different angles. A computer then combines these images into a detailed, cross-sectional view that shows any abnormalities or tumors. A CT scan can also be used to measure the tumor’s size. Sometimes, a special dye called a contrast medium is given before the scan to provide better detail on the image. This dye can be injected into a patient’s vein or given as a pill to swallow.

Visual field exam: A large pituitary gland tumor may press on the optic nerves, which are located above the pituitary gland. In this test, the patient is asked to find points of light on a screen, using each eye separately. The most common visual field problem caused by a pituitary gland tumor is loss of the ability to see objects along the outside of the person’s field of vision.

Treatment for Pituitary Tumors

The treatment for a pituitary tumor will depend on many factors, including:

- The location of the tumor

- Whether the pituitary tumor produces excessive amounts of a specific hormone

- The patient’s general health and preferences regarding potential treatment options

Because having a pituitary tumor can affect many different organs and systems in the body, doctors from several medical specialties will work together to develop a customized treatment plan for the patient.

- Medication (drug therapy)

- Observation

- Radiation therapy

- Surgery

Medication (Drug Therapy) for Pituitary Tumors

Medication (drug therapy) is very effective for treating some hormone-producing pituitary tumors. The medication can stop a tumor from producing excess hormones or shrink it so it does not press on the pituitary gland or other parts of the nervous system.

Medications (drug therapy) commonly used to treat pituitary tumors:

If medications are necessary to treat a pituitary tumor or to help control hormones after surgery or radiation therapy, or to substitute any missing hormones, the patient will take these at home. Medicines used to treat pituitary tumors include:

- Bromocriptine and cabergoline for pituitary adenomas called prolactinomas, which produce too much of the hormone prolactin. These medications can treat prolactinomas by decreasing prolactin secretion and often shrink the tumor.

- Somatostatin analogs (for example, Lanreotide®, Octreotide®) for pituitary adenomas that produce excess growth hormone. Somatostatin analog drugs decrease growth hormone production and may decrease the size of the tumor. These medications can also be used to treat pituitary adenomas that produce excess thyroid hormone. Pegvisomant (Somavert®) blocks the effect of excess growth hormone on the body.

- Ketoconazole (Nizoral®) for pituitary tumors that cause a round face, hump between the shoulders or other symptoms of the body producing too much cortisol, a natural steroid hormone. This medication decreases cortisol secretion but does not shrink the tumor or stop hormone production.

Observation

Observation means seeing a neurosurgeon or endocrinologist and having imaging tests performed periodically. Treatment may be necessary later, for example, if the pituitary tumor grows or symptoms worsen.

Surgery for Pituitary Tumors

Surgery is the most common treatment for pituitary tumors. If the pituitary tumor is benign and in a part of the brain where neurosurgeons can safely completely remove it, surgery might be the only treatment needed ranssphenoidal surgery: This is the most common way to remove pituitary tumors. Transsphenoidal means that the surgery is done through the sphenoid sinus, a hollow space in the skull behind the nasal passages and below the brain. The back wall of the sinus covers the pituitary gland.

For this approach, the neurosurgeon makes a small incision along the nasal septum (the cartilage between the 2 sides of the nose) or under the upper lip (above the upper teeth). To reach the pituitary, the surgeon opens the boney walls of the sphenoid sinus with small surgical chisels, drills, or other instruments depending on the thickness of the bone and sinus. A newer approach is to use an endoscope, a thin fiber-optic tube with a tiny camera lens at the tip. In this approach, the incision under the upper lip or the front part of the nasal septum is not needed, because the endoscope allows the surgeon to see well through a small incision that is made in the back of the nasal septum. The surgeon passes instruments through normal nasal passages and opens the sphenoid sinus to reach the pituitary gland and remove the tumor. The use of this technique is limited by the tumor’s position and the shape of the sphenoid sinus.

The transsphenoidal approach has many advantages. First, no part of the brain is touched during the surgery, so the chance of damage to the brain is very low. There is also no visible scar. But it’s hard to remove large tumors this way. When the surgery is done by an experienced neurosurgeon and the tumor is a microadenoma, the cure rates are high (greater than 80%). If the tumor is large or has grown into the nearby structures (such as nerves, brain tissue, or the tissues covering the brain) the chances for a cure are lower and the chance of damaging nearby brain tissue, nerves, and blood vessels is higher.

Minimally-invasive endonasal endoscopic surgery for pituitary tumors:

Neurosurgeons at the Johns Hopkins Pituitary Tumor Center can remove nearly all benign pituitary tumors using endonasal endoscopic surgery. This minimally-invasive approach enables neurosurgeons to:

- Remove tumors and lesions through the nose and sinuses, without cutting the face or the skull

- Access areas of the brain that are difficult to reach with traditional surgery

Neurosurgeons perform the procedure using an endoscope, a small telescope-like device equipped with a high-resolution video camera and a bright light. To remove a tumor or take a sample of it (a biopsy), they attach special instruments to the endoscope. Benefits of endonasal endoscopic surgery: Endonasal endoscopic surgery:

- Results in less pain and a faster recovery than traditional surgery

- Does not leave a visible scar on the face or scalp

- Allows the patient to start radiation therapy, if needed, almost immediately, without waiting for incisions to heal

Craniotomy: For larger or more complicated pituitary tumors, a craniotomy may be needed. In this approach the surgeon operates through an opening in the front and side of the skull. The surgeon has to work carefully beneath and between the lobes of the brain to reach the tumor. Although the craniotomy has a higher chance of brain injury than transsphenoidal surgery for small lesions, it’s actually safer for large and complex lesions because the surgeon is better able to see and reach the tumor and nearby nerves and blood vessels.

Possible side effects of surgery

Surgery on the pituitary gland is a serious operation, and surgeons are very careful to try to limit any problems either during or after surgery. Complications during or after surgery such as bleeding, infections, or reactions to anesthesia are rare, but they can happen. f surgery causes damage to large arteries, to nearby brain tissue, or to nerves near the pituitary, in rare cases it can result in brain damage, a stroke, or blindness.

Damage to the meninges can also lead to leakage of cerebrospinal fluid (the fluid that bathes and cushions the brain) out of the nose. Until this heals, a person can get meningitis, which is infection and inflammation of the meninge

Diabetes insipidus (discussed in Signs and Symptoms of Pituitary Tumors) may occur right after surgery, but it usually improves on its own within 1 to 2 weeks after surgery. If it is permanent, it can be treated with a desmopressin nasal spray.

Damage to the rest of the pituitary can lead to other symptoms from a lack of pituitary hormones. This is rare after surgery for small tumors, but it may be unavoidable when treating some larger macroadenomas. If pituitary hormone levels are low after surgery, this can be treated with medicine to replace certain hormones normally made by the pituitary and other glands.

- cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak: the fluid surrounding the brain can escape through a hole in the dura lining the skull. In 1% of transsphenoidal cases, a clear watery discharge from the nose, postnasal drip, or excessive swallowing occurs; may require surgery to patch the leak.

- meningitis: an infection of the meninges often caused by CSF leak.

- sinus congestion: small adhesions can stick together and form scars that block air flow through the nose.

- nasal deformity: caused by bone removal or adhesions; may be corrected by surgery.

- nasal bleeding: continued bleeding from the nose after surgery occurs in less than 1% of patients. May require surgery to correct.

Follow-up care

If you had a functional (hormone-making) pituitary adenoma, hormone measurements can often be done within days or weeks after surgery to see if the treatment was successful. Blood tests will also be done to see how well the remaining normal pituitary gland is functioning. If the results show that the tumor was removed completely and that pituitary function is normal, you will still need periodic visits with your doctor. Your hormone levels may need to be checked again in the future to check for recurrence of the adenoma. Regardless of whether or not the tumor made hormones, MRI scans are often done as a part of follow-up. Depending on the size of the tumor and the extent of surgery, you may also be seen by a neurologist to check your brain and nerve function and an ophthalmologist (eye doctor) to assess your vision.